The Algorithm Behind Adaptive Learning

Why most "adaptive" platforms aren't, and how to build one that actually is

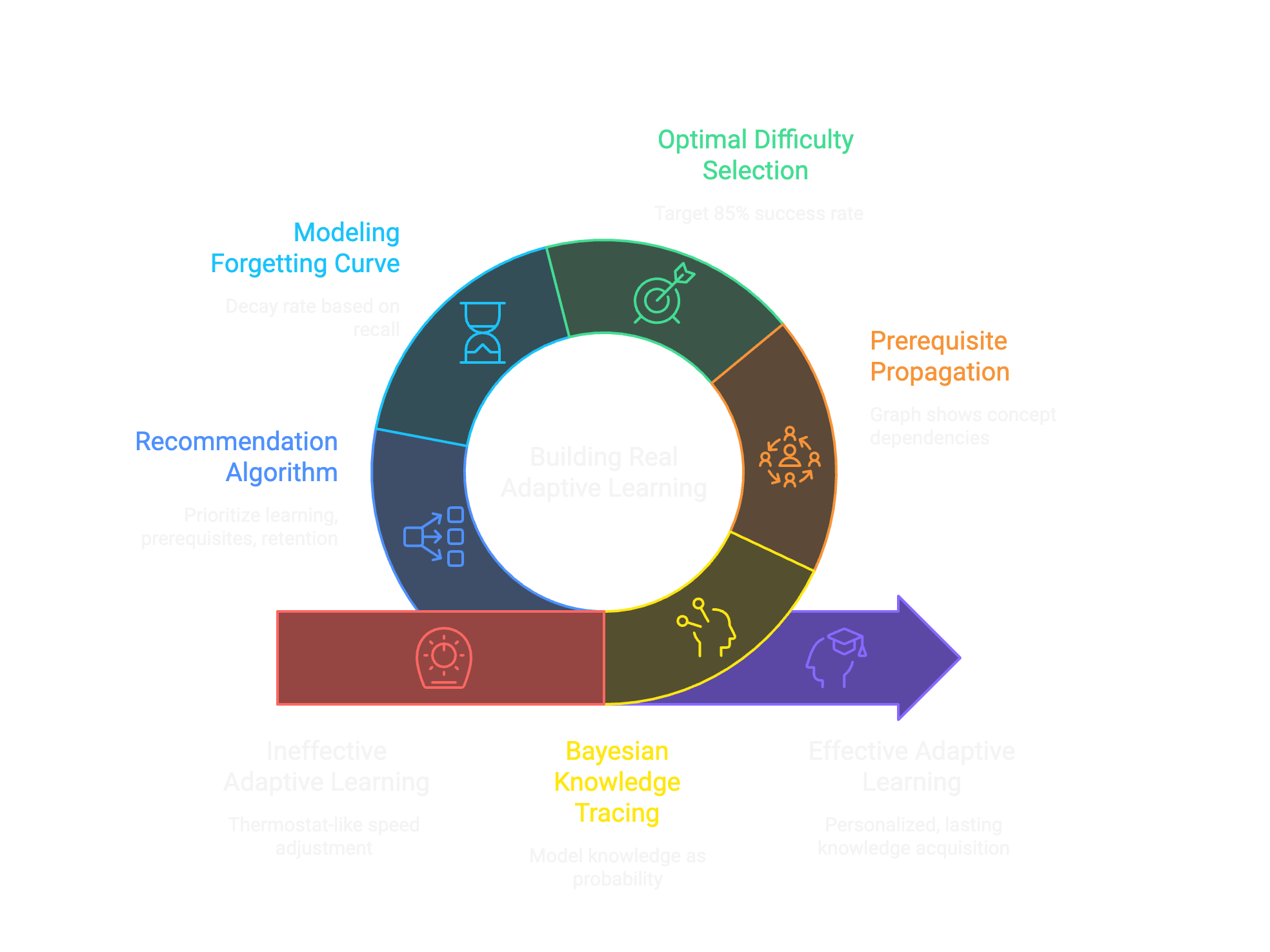

Every EdTech product claims to be "adaptive." Student gets a question wrong? Show an easier one. Student gets three right in a row? Speed up. That's not adaptation. That's a thermostat.

Real adaptive learning requires modeling what each student knows, what they don't, and (critically) why they're struggling.

When we built MathPractice.ai, we didn't want another speed-adjustment system. We wanted software that could do what a great tutor does: identify gaps, trace them to root causes, and build understanding systematically.

Here's how the algorithm actually works.

Why most adaptive systems fail

Most adaptive platforms use a simple model: track accuracy per topic, adjust difficulty up or down. Student scores 80% on fractions? They've "mastered" fractions. Move on.

This breaks in three ways:

First, topics aren't independent. A student struggling with algebraic equations might not have a problem with algebra. They might have a gap in fraction operations from two years ago that's silently undermining everything they try to build on top of it.

Second, accuracy alone doesn't capture understanding. A student who gets 70% right by guessing on hard questions and solving easy ones carefully looks the same as one who has solid fundamentals but makes careless errors. These students need completely different interventions.

Third, knowledge decays. A concept mastered in September isn't necessarily retained in January. Without modeling forgetting, you can't build lasting knowledge.

The core insight: knowledge as probability

The core insight is that knowledge isn't binary. A student doesn't simply "know" or "not know" something. They have a probability of successfully applying a concept, which varies by context and degrades over time without reinforcement.

For each concept in the knowledge graph, I track a probability estimate, essentially asking: "If I gave this student a question on this concept right now, what's the probability they'd get it right?"

This probability updates with every interaction:

P(mastery | correct answer) =

P(correct | mastery) × P(mastery) / P(correct)

Where:

P(correct | mastery) ≈ 0.95 (even experts make mistakes)

P(correct | no mastery) ≈ 0.25 (guessing probability)

P(mastery) = prior estimate from historyThis is Bayesian Knowledge Tracing, adapted. When a student answers correctly, their mastery probability increases. But by how much depends on the question difficulty and their prior estimate. Getting an easy question right barely moves the needle. Getting a hard question right is strong evidence of understanding.

When they answer incorrectly, the probability drops, again weighted by difficulty. Missing an easy question is more damaging than missing a hard one.

How gaps propagate through the graph

Here's where the knowledge graph becomes essential. Every concept has prerequisites: other concepts that must be understood first. Fractions depend on division. Algebra depends on arithmetic. Quadratics depend on factoring, which depends on multiplication and the distributive property.

The algorithm doesn't treat these as independent estimates. Instead, a student's mastery of downstream concepts is bounded by their mastery of prerequisites.

P(concept) ≤ min(P(prerequisite₁), P(prerequisite₂), ...) × weight

Example:

P(solving_linear_equations) ≤

min(P(variable_operations), P(inverse_operations)) × 0.95This creates a crucial behavior: when a student struggles with a downstream concept, the algorithm looks backward through the graph to find where the chain is weakest.

A student who can't solve equations might not need more equation practice. They might need to shore up fraction arithmetic that's been quietly failing them.

The visualization makes this tangible. When you color the knowledge graph by proficiency, you can literally see gaps propagating forward. Red nodes create yellow and red downstream, while green nodes remain isolated pockets of understanding that can't connect to new material.

Finding the zone of proximal development

Not all practice is equal. Questions that are too easy don't teach anything. Questions that are too hard just frustrate. The goal is to find the "zone of proximal development": questions that are challenging but achievable.

I model this using a target success probability. Research suggests optimal learning happens around 85% success: hard enough to require effort, easy enough to avoid discouragement.

target_success_rate = 0.85

For each available question:

predicted_success = f(student_mastery, question_difficulty)

error = |predicted_success - target_success_rate|

Select question that minimizes errorThe difficulty calibration comes from Item Response Theory. Each question has a difficulty parameter estimated from aggregate student performance. A question that 90% of students get right is easier than one that 40% get right. But the model also considers which students got it right. If high-ability students failed it while lower-ability students succeeded, something's off with the question itself.

This creates a feedback loop: as more students attempt questions, difficulty estimates become more accurate, and question selection becomes more precise.

Why knowledge decays (and how to fight it)

Knowledge decays. Ebbinghaus documented this in 1885, and every student who's crammed for an exam and forgotten everything a week later has rediscovered it.

The algorithm models this explicitly. Mastery probability decays over time since last practice:

P(mastery, t) = P(mastery, t₀) × e^(-λ × (t - t₀))

Where:

λ = decay rate (varies by concept and student)

t₀ = time of last practice

t = current timeThe decay rate isn't fixed. It decreases with repeated successful recall. A concept practiced once fades quickly. A concept practiced correctly five times over increasing intervals becomes stable.

This is spaced repetition, but integrated with the knowledge model rather than applied as a separate system. The algorithm doesn't just schedule reviews at arbitrary intervals. It schedules them when the probability estimate is about to drop below a threshold, accounting for the student's demonstrated retention rate for that specific concept.

The result: students spend time on what they're about to forget, not on what they already know or have already forgotten.

The recommendation engine

With all these components, the recommendation algorithm weighs multiple factors:

1. Learning efficiency

Prioritize concepts where practice will create the most improvement, usually those at moderate mastery levels where the student can succeed with effort.

2. Prerequisite readiness

Don't recommend a concept if its prerequisites are weak. First shore up the foundation, then build on it.

3. Retention urgency

Concepts about to decay below threshold get priority. Maintaining knowledge is as important as building it.

4. Goal alignment

If the student has a target (e.g., "prepare for geometry"), weight concepts on the path to that goal.

The algorithm computes a score for each concept and returns a ranked list. The student might see "Recommended: Fraction multiplication (strengthens your foundation for algebraic fractions)" rather than just "Practice fractions."

What this makes possible

With this model, the system can do things simple adaptive platforms can't:

Diagnose root causes. A student struggling with trigonometry might have a gap in ratios and proportions. The system can identify this and recommend remediation, even if the student never explicitly failed a ratios question.

Predict struggle before it happens. If a student is about to start quadratics but has weak factoring skills, the system knows this will be a problem and can intervene proactively.

Build lasting knowledge. Spaced repetition ensures concepts don't just pass through short-term memory. Students retain what they learn.

Personalize at scale. Every student gets a different path through the material, optimized for their specific knowledge state, without requiring human tutors to make these decisions.

Making it work in real-time

One challenge with this approach: computation. The knowledge graph has hundreds of concepts. Updating probabilities, propagating through prerequisites, computing decay, scoring recommendations. All of this has to happen in real-time, on every interaction.

The solution is aggressive caching and lazy evaluation. Mastery estimates are cached until invalidated by new data. Prerequisite propagation uses topological sorting to update only affected downstream nodes. Decay calculations batch efficiently. The recommendation score computation is parallelized.

On the client side, the algorithm runs in the browser for instant feedback. Heavy computation happens server-side asynchronously and syncs back. The student never waits.

What we'd do differently

Simpler decay model first. We built a sophisticated forgetting curve before we had enough data to calibrate it properly. A simpler "review after N days" approach would have worked initially. We could have added the exponential decay model later when we had retention data to validate it.

More explicit feedback to students. The algorithm knows why it's recommending something, but we don't always surface that reasoning. "Practice this because your prerequisite is weak" is more motivating than just "Practice this." We're still iterating on how to make the model's logic visible without overwhelming users.

Earlier teacher dashboards. The algorithm optimizes for individual students, but teachers need aggregate views: which concepts is the whole class struggling with? We prioritized the student experience first, but teachers are often the ones who decide whether to adopt a tool. Their needs should have been parallel, not sequential.

The real lesson

Real adaptive learning isn't about adjusting speed. It's about modeling knowledge: what students know, what they're ready to learn, and what's holding them back. The algorithm combines Bayesian knowledge tracing, knowledge graph propagation, item response theory, and spaced repetition into a unified model.

First principles matter. We didn't start with "what features do competitors have?" We started with "what would a great tutor do, and how can we model that computationally?" The result is a system that's genuinely different, not just another speed dial.

You can explore the knowledge graph and see the proficiency model in action at mathpractice.ai.